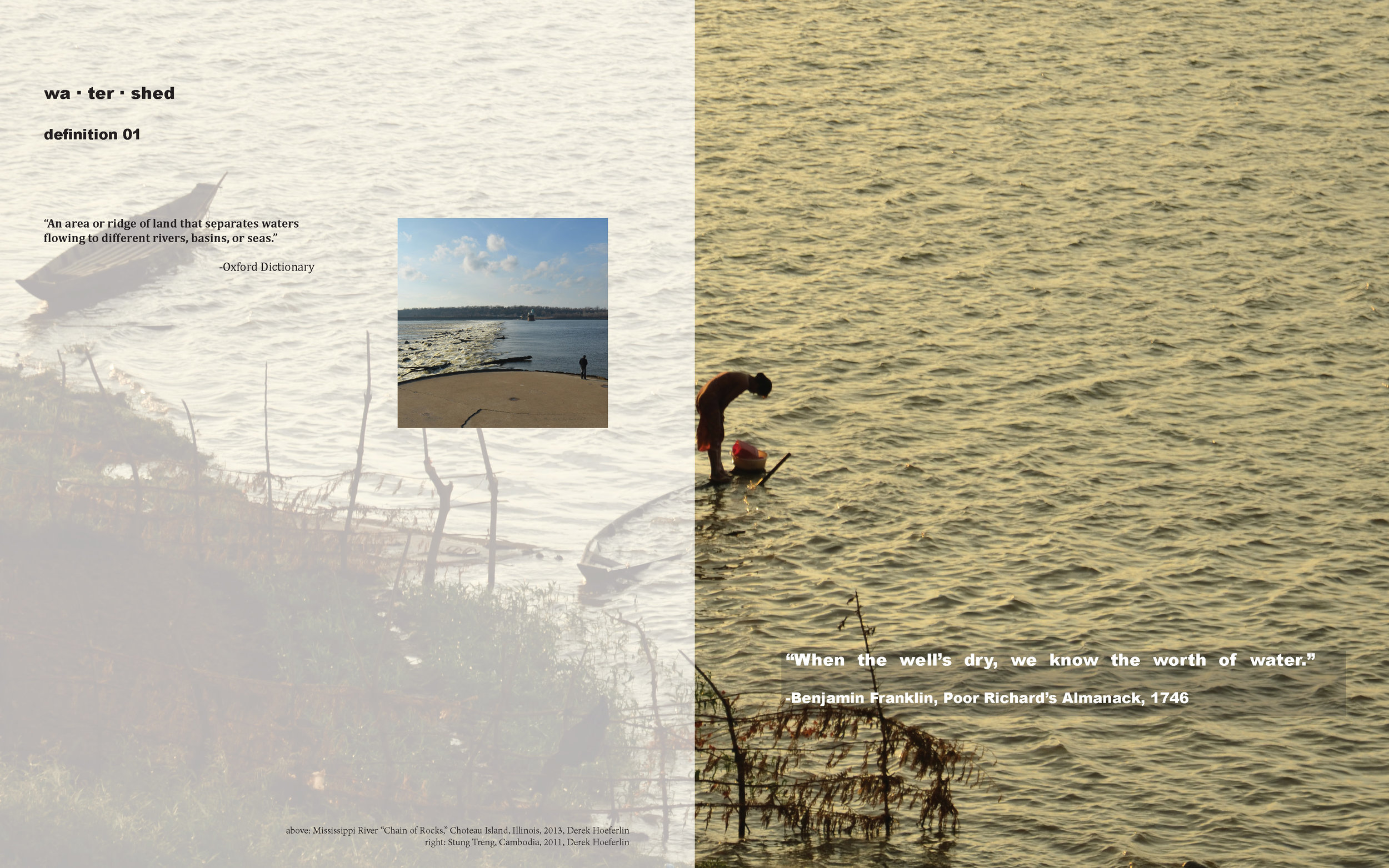

wa · ter · shed

definition 01

"An area or ridge of land that separates waters flowing to different rivers, basins, or seas."

-Oxford Dictionary

wa · ter · shed

definition 02

“an event or period marking a turning point in a situation in a course of action or state of affairs”

-Oxford Dictionary

Watershed = Flows + Tipping Points

[WBB] questions why a watershed's principle definition is "an area or ridge of land that separates waters flowing to different rivers, basins, or seas" (Oxford Dictionary). The scientist geographer John Wesley Powell contextualized watersheds further, with his ubiquitously referenced view:

“that area of land, a bounded hydrological system, within which all living things are inextricably linked by their common water course and where, as humans settled, simple logic demanded that they became part of a community” (Powell 1875).

Powell emphasizes a watershed's potential to prioritize a community's interaction -- and I would add manipulation -- within the hydrological boundary of a certain scaled watershed. In other words, what Shafiqul Islam and Lawrence E. Susskind, in Water Diplomacy: A Negotiated Approach to Managing Complex Water Networks, interpret as the coupling of the natural and societal domains. But for designers, what skill-sets can we contribute to better enable a watershed's integration within the realities of the built environment, many of which do not obey the logic of hydrological boundaries? And by extension, how can a better appreciation for watersheds make us better designers? These realities include the need for designers to engage contested issues such as architecture, infrastructure, landscape, urbanism, regimes of control, societies, and climatic and/or geo-political influences, all of which may reside within or outside of a watershed.

The alternate, and possibly just as important definition for a watershed, is “an event or period marking a turning point in a situation in a course of action or state of affairs” (Oxford Dictionary). A definition not about water per se, but rather one having to do with major jolts, or minor glitches, in what seem to be ordinary states of affairs. Think major jolts like a hurricane, or minor glitches like a tweet. Either have consequence, be them positive or negative, visible or invisible, immediate or distant, and what Malcolm Gladwell refers to as "that magic moment...and spreads like wildfire."

ar · chi · tec · ture

definition 01

“the art or practice of designing and constructing buildings”

-Oxford Dictionary

ar · chi · tec · ture

definition 02

“the complex or carefully designed structure of something”

-Oxford Dictionary

Architecture = Buildings + Complexity

[WBB] questions why architecture’s principle definition is the “practice of designing and constructing buildings” (Oxford Dictionary). Although this disciplinary strength remains the priority for most practicing and aspriring architects, it also reinforces the discipline potentially operating in a silo, and dangerously out of touch. Maybe a more pertinent question is: what really constitutes a “building?”

The National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) elaborates for what licensed architects are responsible:

“Licensed professionals trained in the art and science of the design and construction of buildings and structures that primarily provide shelter. An architect will create the overall aesthetic and look of buildings and structures, but the design of a building involves far more than its appearance. Buildings also must be functional, safe, and economical and must suit the specific needs of the people who use them. Most importantly, they must be built with the public’s health, safety and welfare in mind.” (NCARB)

The last sentence is crucial. Not only is it a legal mandate, one at least in the United States, it raises three important external influences -- health, safety, welfare. These are complexities that can be considered outside of the realm -- or enclosure -- of a building. [WBB] argues that these can only be understood with a new appreciation for both watersheds and architecture.

Water knows no boundaries. Buildings tend to want boundaries.

The alternate definition for architecture, “the complexity or carefully designed structure of something” (Oxford Dictionary), albeit ridiculously vague, is quite provocative for the discipline of architecture, and considered heresy to those that believe that architecture can only be practiced by a licensed architect, and as such, only an architect can design buildings. This is primarily for legal reasons, but many perceive this liberal use of the term as a threat to the discipline. But let’s face it, most of the built environment is not even stamped by a licensed architect. So if we suspend what can be argued to be an archaic view of the discipline, architecture no longer is about just designing buildings. Rather, architecture is more encompassing, and about designing complex, careful structures. So [WA] contends that architecture does not need to be the creation of the hand of an architect. And more interestingly, the potential of this definition leads to the engagement of a more complex approach to architecture, and for the case of [WA], the “something” is water. Islam and Susskind argue for a diplomatic approach to “manage water networks” and contend that “water problems are complex...are not easily knowable, and are usually unpredictable” and cannot be solved by “reductionism” or “systems engineering.” Rather, “water resources might be more effectively managed if understood more about the interaction and feedback among components of the relevant natural, societal, and political systems.” This liberation of “unpredictability” may be what holds most potentiality for designers in relation to water.

As I challenge the architecture discipline to better engage watersheds and issues outside of the building envelope, in 2013, landscape architect Rod Barnett challenged the landscape architecture discipline to better engage a theory of emergence. In his book Emergence in Landscape Architecture, Barnett builds upon the ideas of Bruno Latour, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, explaining:

“Emergence theory can help us understand the world not as an object or a process to be known, observed or represented, but as a dynamic, shifting assemblage in which humans, plants, animals, rivers, clouds, trees, suburbs, subways, heritage districts and all manner of other things are embedded, shifting and unfolding along with everything else.”

I am not arguing for [WA] to be a substitute for what the architecture or landscape architecture disciplines already accomplish so well, or a substitute for any specific design discipline for that matter. Rather, I am arguing for [WA] to be a flexible road map for various disciplines to better engage water-based design, and in doing so by adding one’s own disciplinary strength, productively learn from other disciplines.

[WA] = Opportunities not Crises

Pessimistically, our collective 21st century crisis in regards to the built environment is climate change, and more specifically, in relation to water-based disasters. If we couple these challenges with our globally failing physical and social infrastructures, the future is indeed grim.

Optimistically, what if we disregard our archaic, reactive, crises-driven design approaches and re-orient to accommodate climate change, and in doing so to adapt with sea level rise, to transform wastes to resources, to live with the water, and so forth? What if watersheds and architecture combine as a new and proactive design framework, potentially even as a new discipline, one that prioritizes contemporary water opportunities and tipping points in time that are way beyond our historically, conventional understandings of such.

[WA] = Proactive not Reactive

Life and society depend upon water. We often fail to appreciate that the molecular connection is so essential. Recent human-altered water-based catastrophes in the USA alone such as hurricanes, floods, droughts, dam failures, contaminations, and wildfires place front-and-center that our technological supremacy over water can have unintended, and oftentimes disastrous, effects. We are repetitively reactive, rather than positively proactive. The status quo is economically, environmentally, and socially unacceptable. Additionally, water may be the most politicized commodity on earth. But as Jane Wolff once told me, “water is apolitical.” In other words, water ultimately flows where water wants to flow. Water always wins. Take the New Orleans region as an example. The city and surrounding Louisiana Delta have become ground zero for all things human-made-water disasters — hurricanes, floods, oil spills, sinking lands, disappearing wetlands, rising seas and yes, even droughts. However, it is important that New Orleans is not alone. Water is a continental issue and of course water is a global issue. Water, if not already so, will become the global crisis. But there is an alternate way. We need to anticipate (design as foresight), rather than wait (design as hindsight).

[WA] = Downstream + Upstream

In the face of uncertain issues of climate change, extreme weather, sea-level-rise, water scarcities, and population fluctuations that are both exploding and depleting, significant attention has been brought to the comparative studies of deltas and their urbanized developments. Known as “delta urbanisms,” these water-rich regions arguably are the economic life-blood of most nations’ economies. However, [WA] argues it is crucial to take a bigger step back and understand deltas and their urbanisms, not just within and compared among themselves, but also within their larger, cause-and-effect, distribution contexts of watersheds, or more technically, river basins. Upstream is the starting point, not downstream at the delta. [WA] argues for shifting priorities upstream.

[WA] = Pragmatism + Optimism

But since I am an optimist architect, I truly believe that deltas, their urbanisms, and their much larger scale distributive river basin scale contexts must be the models for what my design collaborator Ian Caine and I define as 21st and 22nd century hydro-regions. But this optimism is not foolhardy idealism. Actually, it is rather pragmatic. In other words, hydro-regions, up and down entire river basins, must get their fundamentals straight. These fundamentals first begin with a return to basics: a foundational understanding that water is the primary component of the actual ground that is occupied.

[WA] = Bigness + Katrina (Way Beyond Bigness)

For context, two moments have led me to question my role as an architect in relation to larger, contemporary issues of the built environment.

1) The publishing of S,M,L,XL in October 1995, featuring Rem Koolhaas’ manifesto Bigness: Or the Problem of the Large.

2) The landfall of Hurricane Katrina just outside of New Orleans in August 2005.

In Bigness, Rem Koolhaas specifically challenged architects, and one can argue by extension landscape architects, urban designers, planners and other design disciplines, to “surrender” to complex modes of technologies, to politics and economics, set within what were then emerging issues of globalization in the 1990’s, that is emerging at least to the architecture discipline. Koolhaas charged, “…The makers of Bigness are a team (a word not mentioned in the last 40 years of architectural polemic).” 01

Then too, Hurricane Katrina catapulted the fields of design into an unprecedented man-altered “natural disaster,” and within such, challenged designers to prove their relevance. Although still the costliest “natural disaster” in USA history, we would soon realize that Hurricane Katrina was not just a one-off, and one just only specific to the Gulf Coast of the United States, or other coastal contexts for that matter. Since Katrina in 2005, and especially since 2008, frequent extreme weather events and water-related catastrophes in the United States—both coastal and inland—have repeated over and over again. Couple this with the accelerating realities of the effects of climate change in the US and elsewhere, we can only assume more extremes will continue with intensity, and do so relentlessly.

Koolhaas makes only the slightest swipe to water in Bigness, when he referred back to his Delirious New York retroactive manifesto, stating “The architecture relates to the Groszstadt like a surfer to the waves.”02 And obviously, Katrina was almost all about water. However, both are definitely what I define as “watershed,” or tipping point events for the design disciplines, and to be clear, not just limited to the discipline of architecture.

Highlighting events since 2005:

2005: Hurricane Katrina (costliest in US history, 1833 fatalities), Gulf Coast

Hurricane Rita (120 fatalities), Gulf Coast

Hurricane Wilma, Florida (62 fatalities)

2008: Hurricane Gustav, Louisiana (153 fatalities)

Hurricane Ike, Texas (195 fatalities)

Mississippi River spring floods (unknown fatalities)

2010: Deepwater Horizon/BP Oil Spill, Gulf of Mexico (11 fatalities, 1300 miles of oil covered coastal Louisiana, estimated 800,000 bird fatalities)

2011: “Great” Mississippi river spring floods (largest floods since 1927 and 1993 floods)

Midwest tornadoes (553 fatalities, second most since 1925)

Hurricane Irene, Eastern Seaboard (49 fatalities)

2012: Midwest drought

“Superstorm” Sandy, Eastern Seaboard (285 fatalities)

2013: Mississippi river spring floods and winter storms

2014: Mississippi river spring floods and winter storms

2015: California drought and wildfires

2016: Mississippi river winter floods

2017: Mississippi river winter floods

Hurricane Irma, Florida (134 fatalities)

Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico (arguably 2,975 fatalities)

Hurricane Harvey, Texas (82 fatalities)

(The 3 hurricanes totalling the costliest cyclone season on record)

California wildfires

2018: California wildfires

Hurricane Florence, North Carolina (51 fatalities)

Hurricane Michael, Florida (45 fatalities)

2019: California wildfires

And on and on...

By extension, these calamities have challenged design disciplines’ roles in complicated community, political and multi-scale post-disaster contexts. Both “Bigness” and Hurricane Katrina have challenged designers to step up, to engage, and to get out of their bubbles, both academic and professional ones. But how to do so? Can the academic/professional divide truly remain intact to adequately address such challenges? I contend it cannot. Therefore, this is a dilemma that is “Way Beyond Bigness,” or in other words, what we often refer to as a “Gordian Knot.”

But maybe there’s a clue. Can water-based design optimistically engage such “impossible problems,” and in doing so, productively offer new possibilities?

References:

Barnett, R. Emergence in Landscape Architecture. (London and New York: Routledge, 2013).

Franklin, B. Poor Richard's Almanack. (Philadelphia: 1746).

Gladwell, M. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2002).

Islam, S. and Susskind, L.E. Water Diplomacy: A Negotiated Approach to Managing Complex Water Networks. (New York: RFF Press/Routledge, 2013).

Koolhaas, R., "Bigness, or the Problem of the Large," in S,M,L,XL (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 1995).

Oxford Dictionary.

Powell, J.W. The Exploration of the Colorado and Its Canyons. (New York: Penguin Classics, 1875).

Solomon, S. Water: The Epic Struggle for Wealth, Power, and Civilization. (New York: Harper Perennial, 2010).